- Rebekah Mills-Bennett, 34, from Cardiff, underwent the surgery

- Sporting dreams were wrecked after she twisted her left knee at 14

- Had surgery to reconstruct torn ligament but it didn’t knit together properly

- By 30 Rebekah could barely walk a couple of hundred yards

- Orthopaedic surgeon suggested a meniscal transplant

- By Judy Hobson for the Daily Mail

Donor cartilage can be used to help delay or even prevent knee arthritis and the need for a joint replacement. Rebekah Mills-Bennett, 34, a physiotherapist from Cardiff, underwent the surgery, as she tells JUDY HOBSON.

THE PATIENT

As a teenager, I lived for sport. But my dreams of playing volleyball for England were wrecked after I twisted my left knee during team trials when I was 14.

An MRI scan revealed I had ruptured my anterior cruciate ligament, which joins two bones in the knee together.

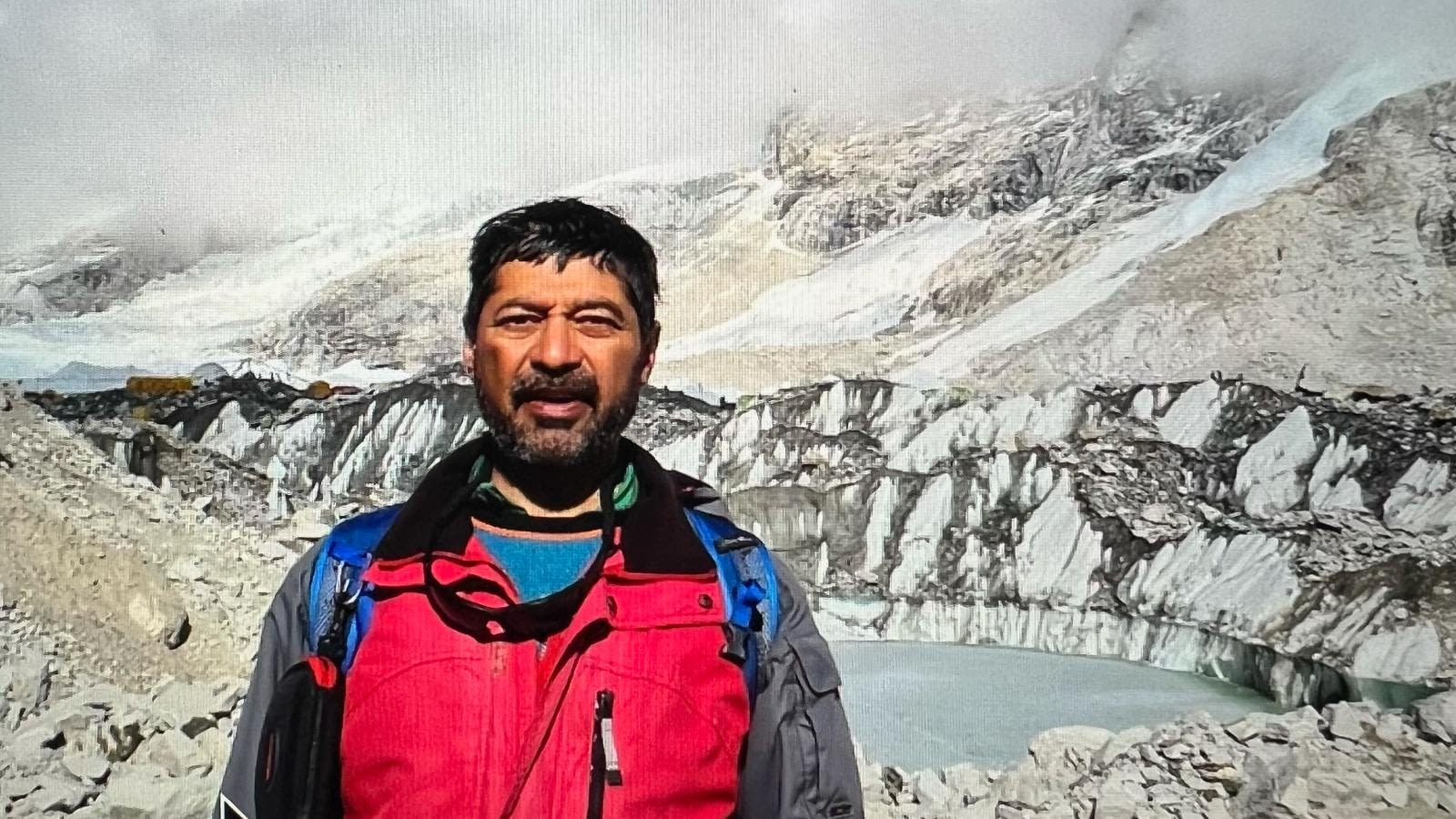

Rebekah could barely walk a couple of hundred yards and was starting to limp

I’d also torn my medial meniscus, a disc of rubbery cartilage on the inner side of my knee, which cushions your knee bones when you bend and straighten your leg.

I had surgery to reconstruct my torn ligament and the torn meniscal cartilage was sewn back together.

However, it didn’t knit together properly and my knee kept swelling up afterwards. So three months later, I had an arthroscopy, where the surgeon uses a telescope with a camera at the end to examine inside the joint, then repairs or removes damaged tissue.

He took out some of my torn meniscus during the procedure. Then because bits of it still kept breaking off, I had a second arthroscopy in 2001 to remove the rest.

This seemed to work well, and in my 20s I was running regularly and playing beach volleyball. But five years ago, my left leg started to become very swollen and painful after exercise.

Eventually, I had to give up sport altogether. I could barely walk a couple of hundred yards and was starting to limp. I was miserable because it was such a huge part of my life. I even thought about having my leg amputated and being fitted with an artificial limb – I knew people with artificial limbs who were taking part in marathons.

At 30, she felt like an old, disabled woman

I was only 30, but I felt like an old, disabled woman. I was planning to marry my fiance, Gareth, a semi-professional rugby player, and was frightened I wouldn’t be able to keep up with him.

In September 2010, my GP referred me to an orthopaedic surgeon, who suggested a meniscal transplant as my knee had started to become arthritic.

I’d not heard of this procedure before, but he said I’d be given a new meniscus donated by someone who had died.

I had to wait six months for a donor as it had to be the correct size and come from someone a similar age. It would come from the U.S. because this is a relatively new procedure and the tissue available in Britain is limited.

It arrived two weeks before I got married in June 2011. I had the operation on June 28 at the Vale Hospital in Hensol, near Cardiff, ten days after my wedding.

The procedure took four hours. Afterwards, the pain was horrendous. I was given the pain-killing drug co-dydramol plus anti-inflammatories, which helped.

The next day, though still in pain, I was out of bed on crutches. I also had to wear a leg brace for eight weeks to stop me from bending my knee too much. On the fourth day, I went home and after six weeks I no longer needed painkillers.

After nine months, I could walk more than a mile pain-free – now it’s five or six miles and I’ve also started to play a little volleyball again. I’m so grateful to the person who donated the meniscus.

THE SURGEON

Christopher Wilson is an orthopaedic surgeon at the Nuffield Health Cardiff Bay and Vale Hospitals in Hensol.

Orthopaedic surgeons now recognise that if you replace a damaged meniscus you can delay knee arthritis – and in some cases prevent it altogether. This is because when your meniscus is damaged, it puts pressure on the rest of the knee and you end up needing a joint replacement.

The meniscus is a crescent-shaped cushion of rubbery, fibrous tissue that sits on either side of your knee joint.

It acts as a shock absorber and allows knee bones to glide smoothly over each other. If it gets damaged, bone starts to rub on bone and you can go on to develop arthritis.

I’ve started to play a little volleyball again. I’m so grateful to the person who donated the meniscus

Tears to the meniscus are common after a fall or any twisting injury. It also loses elasticity through wear and tear as we age.

A meniscal transplant is best done before the surfaces of the joint have become too damaged. For this reason, it is most suitable for people with the signs of early arthritis – usually the under 50s.

In the U.S., surgeons carry out the procedure well before the onset of arthritis and this is proving very successful. We also have 20 years of data from Belgium showing that it has a 90 per cent-plus success rate.

Only 100 to 200 operations are done in the UK each year, but we’re now in a position where we can start conducting our own studies. I’m hopeful that by the end of this decade a meniscal transplant will have become a standard procedure.

Rebekah had the meniscus on the inside of her left knee removed some time ago. She was hobbling around in a lot of pain and showing early signs of osteoarthritis. Without a new meniscus, her symptoms would have worsened rapidly.

The first thing we to do is ensure we get a good size-match from a donor. This is critical because a meniscus can’t be stretched or squashed to fit and cutting damages it so it won’t work as well.

To gauge the size needed, we use an X-ray machine that incorporates a measuring device to look inside the knee.

After nine months, Rebekah could walk more than a mile pain-free – now it’s five or six miles

The donated meniscus looks rather like a horseshoe, and at either end it has tiny natural anchors of stronger tissue. It is these that keep it firmly fixed to the patient’s bone and stop it sliding around.

Using a camera to guide me, I implanted Rebekah’s new meniscus in a keyhole procedure under general anaesthetic. I made four tiny (0.5cm) keyhole incisions and two longer 6cm incisions over the front of her knee.

With a motorised device that looks rather like a pen but acts like a mini-vacuum, I removed the last remaining bits of Rebekah’s own meniscus.

Then I drilled two tiny tunnels into the top of her shin bone, (the tibia) and pulled the meniscal anchors through these and stitched them in place at the front of her knee. After stitching up all the incisions, I injected lots of local anaesthetic around the area to help with the pain.

Rebekah’s transplant has made a huge difference – her chances of ever needing a full knee replacement will have been delayed by at least 15 years.

ANY DRAWBACKS?

The greatest risk associated with this kind of surgery is that it will fail and need to be redone. It is estimated this occurs in 5 to 10 per cent of cases.

There is a very tiny risk of disease, however because donated meniscus discs are all screened for diseases such as hepatitis and HIV, the risk is less than with a blood transfusion, says Adrian Wilson, consultant orthopaedic surgeon at the North Hampshire Hospital in Basingstoke and the Hampshire Clinic in Old Basingstoke.

Rejection of a donor meniscus is rare as there are too few cells in the tissue to excite a response.

‘The reason so few are carried out in the UK is that it is a challenging procedure, so surgeons need to put in the time in order to acquire the expertise,’ adds Mr Wilson. ‘But it can no longer be regarded as experimental and when undertaken makes a massive difference to people’s lives.’

Meniscal transplant surgery is available on the NHS and privately. It costs around £9,000.

Source: http://www.dailymail.co.uk/health/article-2791535/me-operation-cartilage-transplant-save-knees.html