Every year, 30,000 Britons undergo knee replacement surgery. Mark Evans, 50, from Penarth, South Wales, underwent a different procedure. Here, Mark, a widower, with two children aged 14 and 11, talks to Isla Whitcroft about his experience and the surgeon explains the technique.

THE PATIENT

Mark Evans

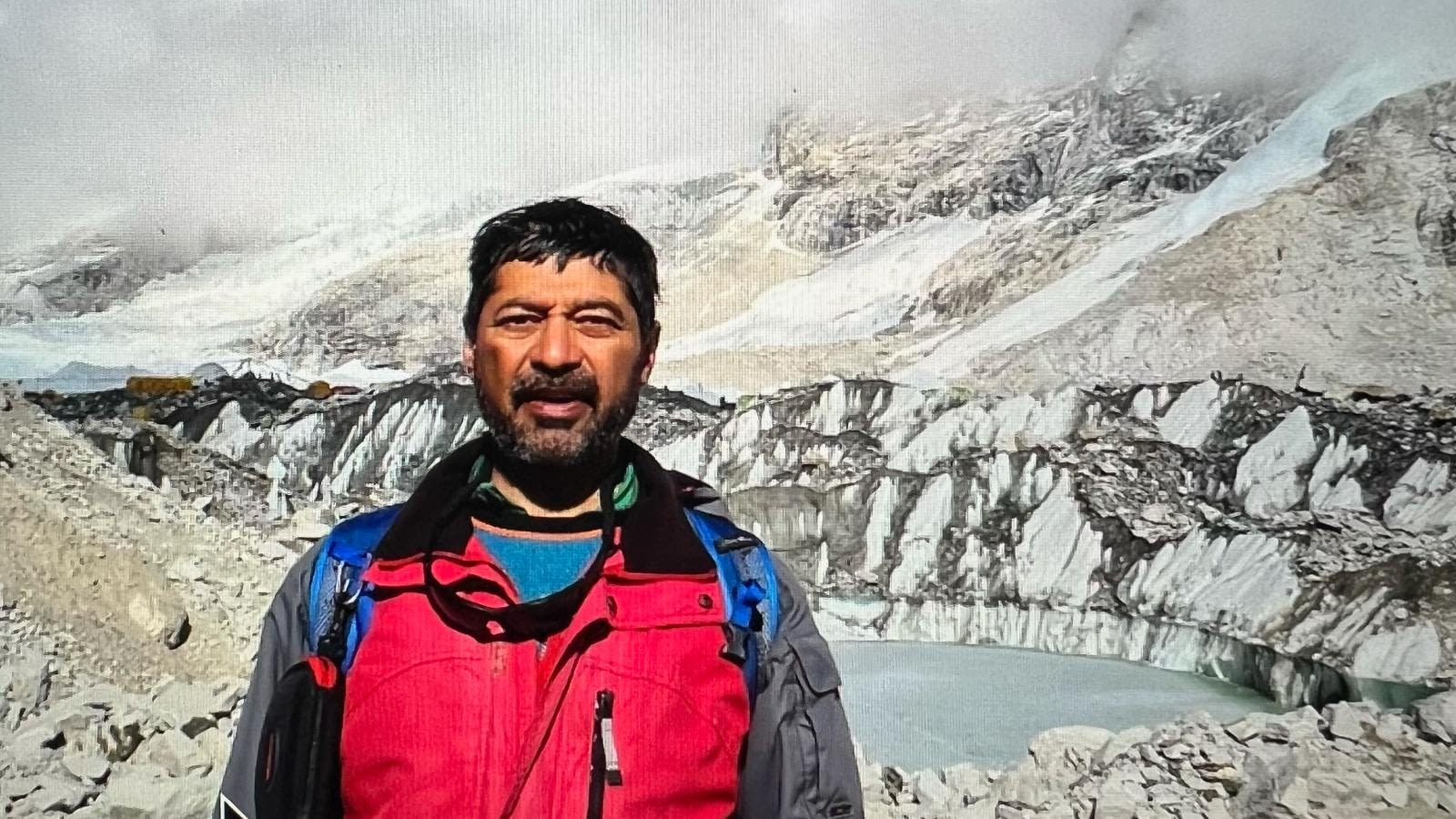

Pain-free: Mark Evans – once plagued with bandy knees – can now play with his children

My left knee has caused me problems since my late 20s. I was always sporty and active, but this came to a halt around 20 years ago after I damaged a ligament; then a small bit of bone broke off.

Surgery sorted that out, but over the following years the knee became painful after I exerted myself – after a long walk, or kicking a football around too long.

I’d never been one for pain killers, so I tried strapping up my knee using bandages and putting my leg up, but nothing really worked.

By 2001, things were getting worse; I was struggling to pick up my little boy and I couldn’t run around after the children without being in pain.

The final straw was three years ago, when my fiancée told me I was bandy legged.

Looking in the mirror I could see she was right. My left leg was bowed out from the hip to the ankle, and you could see it through my trousers.

An X-ray confirmed I had severe osteoarthritis in my left knee. The cartilage cushioning the thigh bone and the shin bone had worn away; in places, bone was rubbing on bone.

I was referred to an orthopaedic surgeon who said I needed a knee replacement, but as I was young he was reluctant to recommend it.

Knee joints only last for ten years or so, and I’d probably need two in my lifetime, major procedures. He sent me away with painkillers.

Two years ago, I decided to seek a second opinion. New scans showed my bandy leg had got even worse: the damage was in the inner-part of my knee.

Protect myself from the pain, my body would automatically roll my leg out. Over time this pushed my knee outwards, creating my bandy leg.

A full or partial knee replacement would have been one answer; but I wouldn’t be able to do active things, such as cycling long distances, jogging or just larking around with my children.

The other option was a high tibial osteotomy – realigning my lower leg bone, the tibia, to make sure my body weight was loaded on to the good part of the knee.

They’d do this by cutting open the bone and propping the gap open with a wedge. At the same time, the correction would straighten out the bandy leg.

This operation can initially be more painful and has a longer recovery time than a joint replacement, but the long-term function is much better and can last considerably longer before you need a new joint.

The operation, in January 2007, took about two hours and when I woke up my leg was covered in bandages and very painful.

I had morphine on a pump for a few hours and was then on prescription painkillers for the next three days.The next morning, I was helped out of bed to use crutches. Two days later, I went home; the first week was spent in bed, with my leg raised up. A week later, my stitches were taken out and, by then, I was down to just aspirin for pain relief. I was on crutches for 12 weeks, although by about week six I was able to put some weight on to my knee, and it felt more stable than it had for years.

The pain I had lived with for so long had gone.

Five months after the operation I went for my first run. I can now run more than 5km at a good pace and play with my children.

It was a long haul but it was definitely a commitment worth making.

THE SURGEON

Chris Wilson is a consultant orthopaedic and trauma surgeon at University Hospital of Wales in Cardiff, and at the Vale Healthcare Cardiff Bay Clinic.

He says… An osteotomy is a surgical technique used to realign bones into a position that takes the pressure off an arthritic joint.

It was the main surgical treatment for osteoarthritis before joint replacements came along in the Seventies.

It fell out of favour because the patient had to be in plaster for months afterwards; these were the days before we had titanium plates to hold healing bones together.

It is also a complicated procedure which takes a reasonable degree of expertise, and there were some pretty bad postoperative results.

Joint replacements seemed the safest option even though the end result in terms of mobility and flexibility may not be as good.

But today, modern surgical techniques and equipment-mean that an osteotomy is now a much safer procedure – it gives a good long-term prognosis in the right patient.

I use them regularly as an alternative to knee replacement in people who, like Mark, aspire to a high-level of activity and knee flexibility. It saves them from having a joint replacement, possibly for years.

Mark had fairly commonplace wear-and-tear of the knee joint. The damage was quite bad, and if he had left it for much longer, he would have been walking with a stick within a few years.He’d been told the only option was a new knee joint, which is a story I hear a lot. This is a pity, because providing the patient meets certain criteria, an osteotomy is a good alternative.

The key is that one side of the knee joint is still good enough to carry the weight usually carried by the entire joint; the patient must also be healthy enough that the bone will heal up quickly – and prepared to commit to a longer recovery time.

MRI scans pinpointed that the damage was on the internal section of the knee joint – the outside section of the joint was actually quite healthy.

After Mark was given a general anaesthetic we put him under an X-ray machine to monitor his leg constantly as we work.

During the operation we create a tiny gap in the bone on the inside of the lower leg; by propping this open we force the knee joint to shift to the outside of the tibia.

I made an 8 in incision on the inside of Mark’s lower leg to expose the top of his tibia, using X-rays and guide wires to make sure I didn’t cut too far. Using a sharp surgical chisel called an osteotome, I then cut directly into the bone just below the knee joint.

Then, I inserted a ‘spreader’ into this cut. This opens up a gap as we turn a screw; the pressure of the gap forces the bone on either side of it to move apart. Gradually, the tibia started to move, then the entire lower leg was pulled into the required position; the head of the tibia was also moving within the knee joint, shifting to the outside of the joint where it was still healthy.I had to open up the gap in Mark’s bone to around 12mm wide, which was quite big. To keep the gap permanently open, I used a wedge of synthetic bone.

This provides a scaffolding for new bone to grow around, and stabilise. I also put a T-shaped titanium plate over the gap and down the tibia.

Finally, after an X-ray to make sure that the bone is securely in its new position I closed the incision.

The muscles and ligaments have to be put back into place carefully and, in some cases, stretched a bit, because the bone is now slightly longer with the addition of the wedge.

Mark has had an excellent result and may not need another knee operation for years. The operation costs the NHS around £2,500; privately it costs up to £5,000.